Solve death with synthetic replacements

We bring together scientists, engineers, entrepreneurs and investors who seek to prolong and enhance human existence

Mission

Sciborg DAO is on a mission to conquer death, enabling the long-term preservation of consciousness while enhancing human capabilities and experiences. We're working to achieve this by developing synthetic replacements that will ultimately provide us the opportunity to become cyborgs.

Our team is a mix of entrepreneurs and scientists, working hand-in-hand with top domain experts. We harness the power of blockchain to crowdsource funds and creativity and drive progress. With governance tokens, our community of contributors plays a direct role in shaping decisions, setting priorities, and pushing the boundaries of what it means to be human.

Strategic Fields

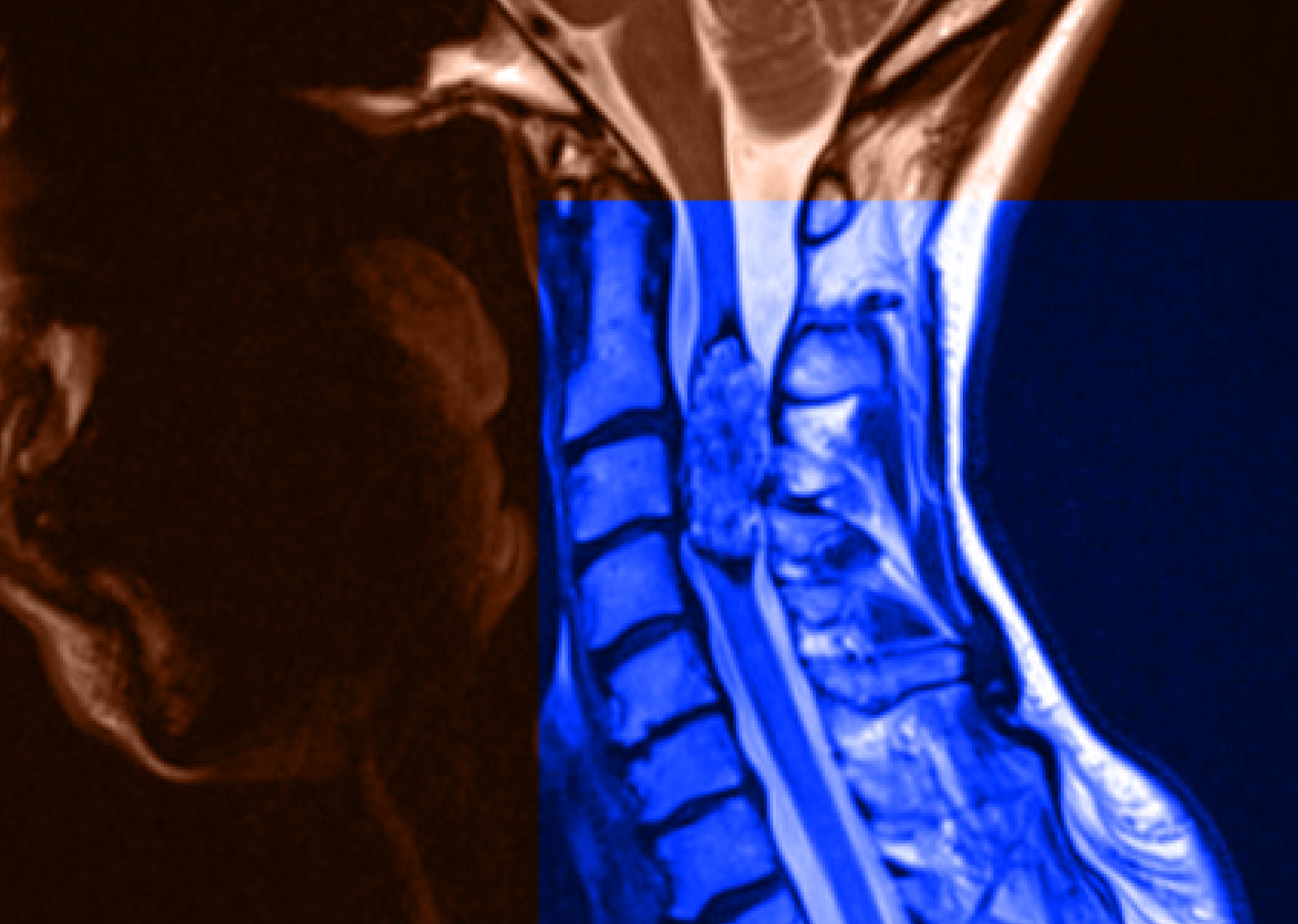

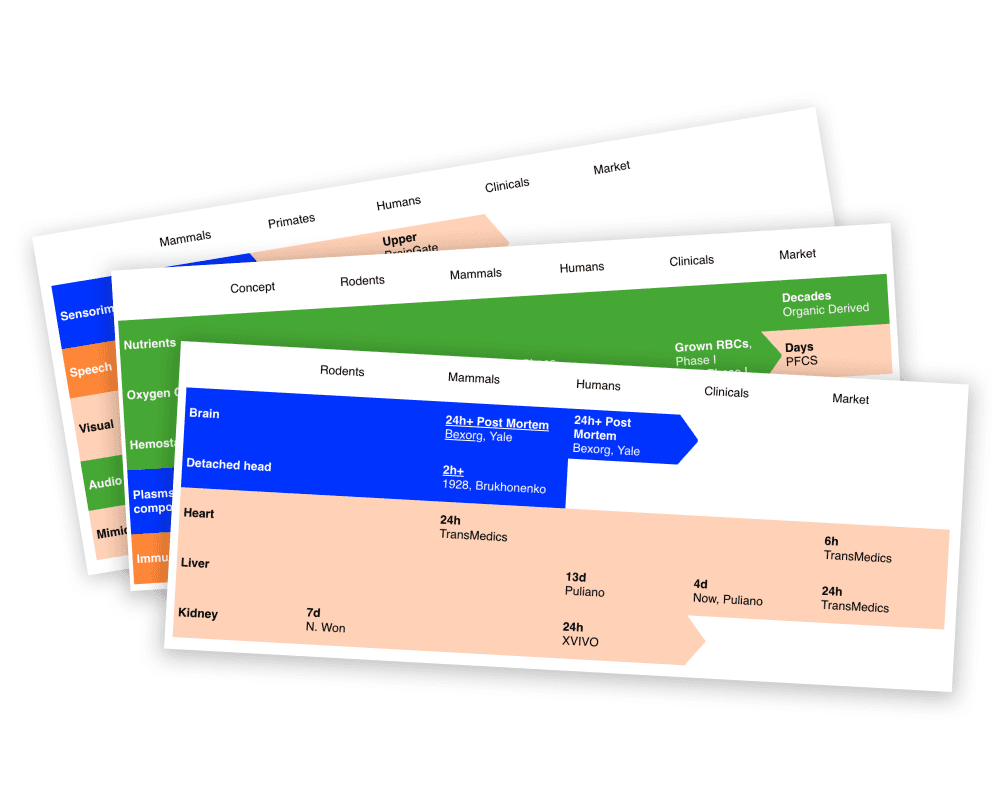

Organ/head perfusion devices

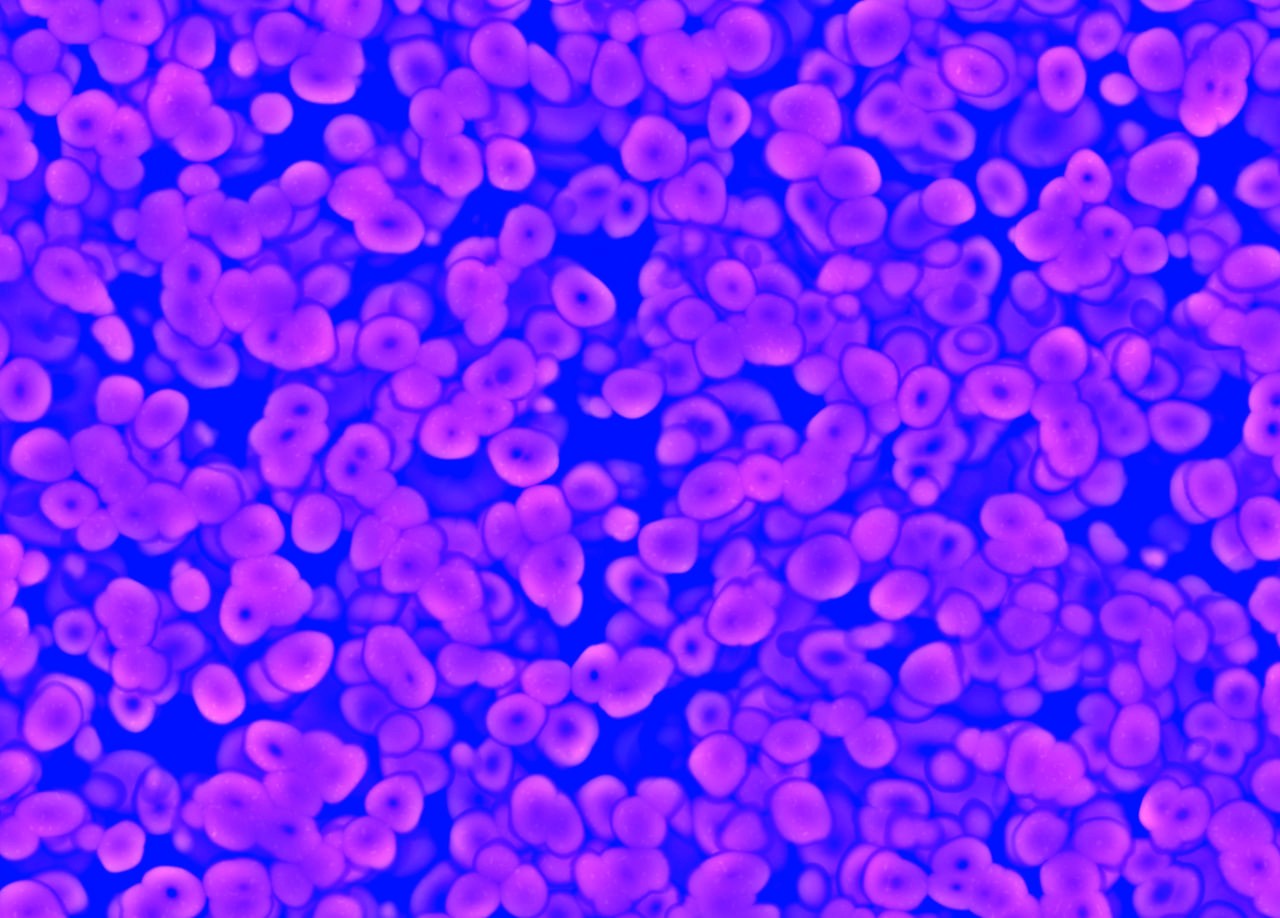

Synthetic blood

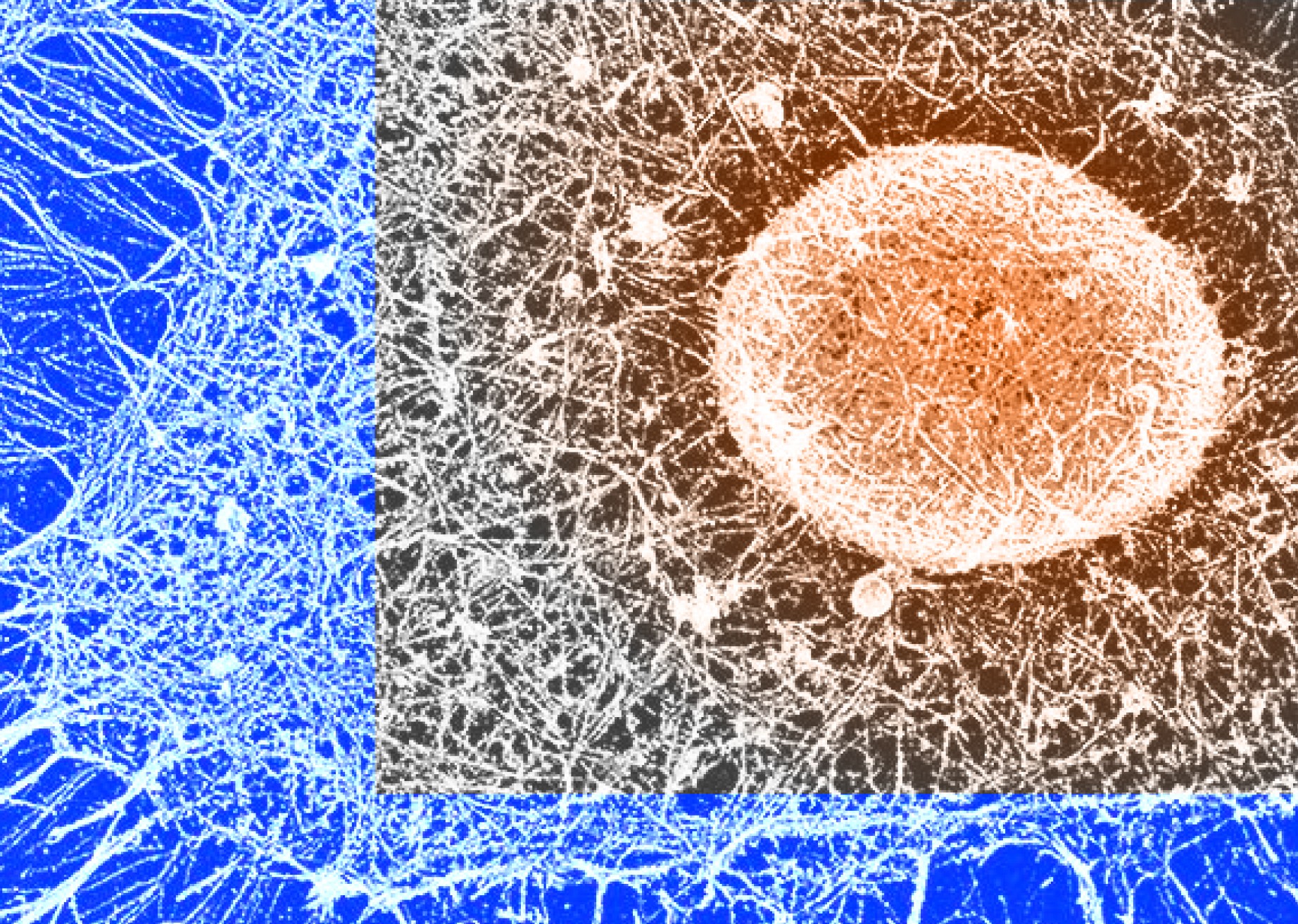

Biohybrid neural interfaces

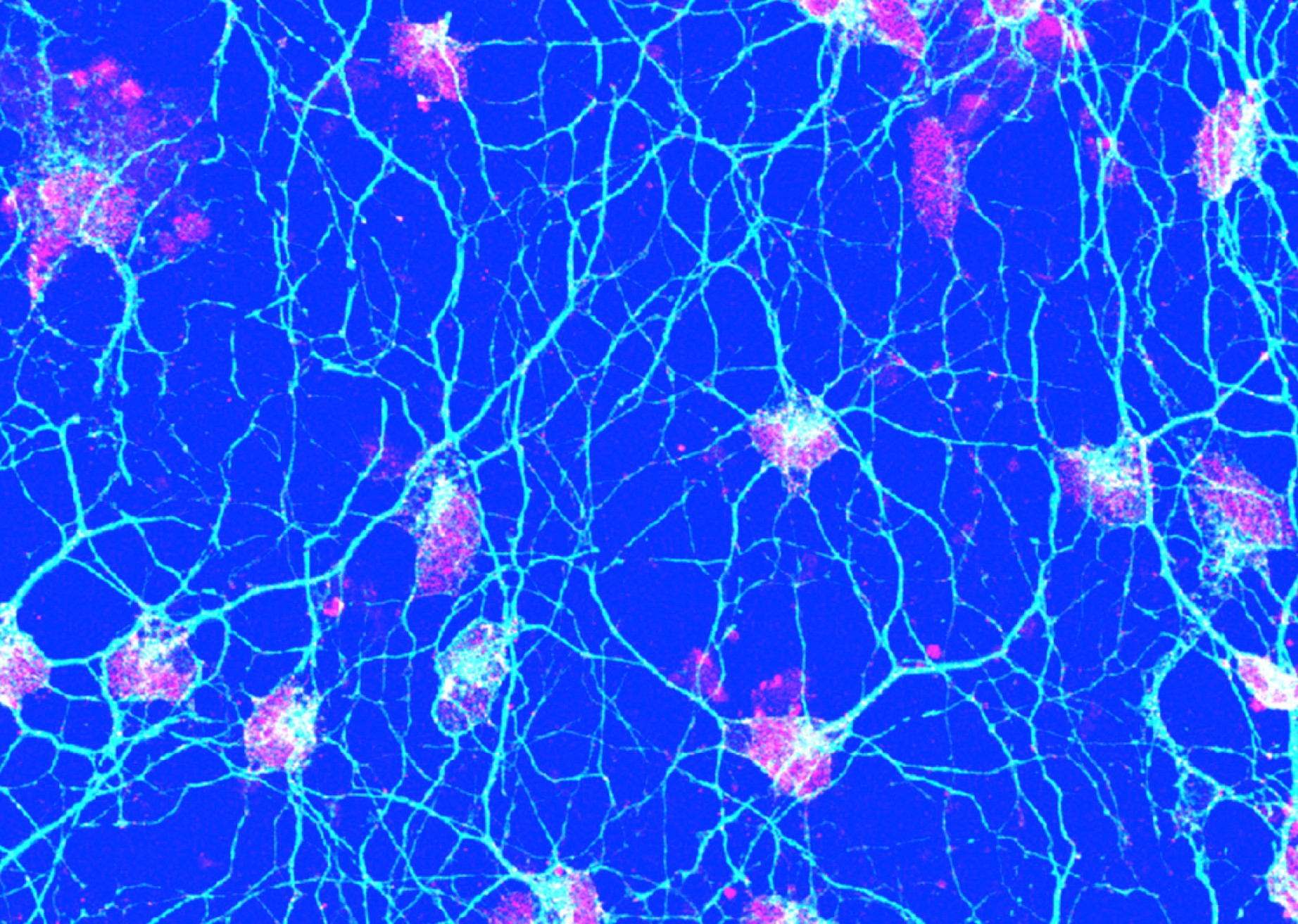

Neuromorphic brain prosthetics

Experimental tests of consciousness theories

Operational Strategy

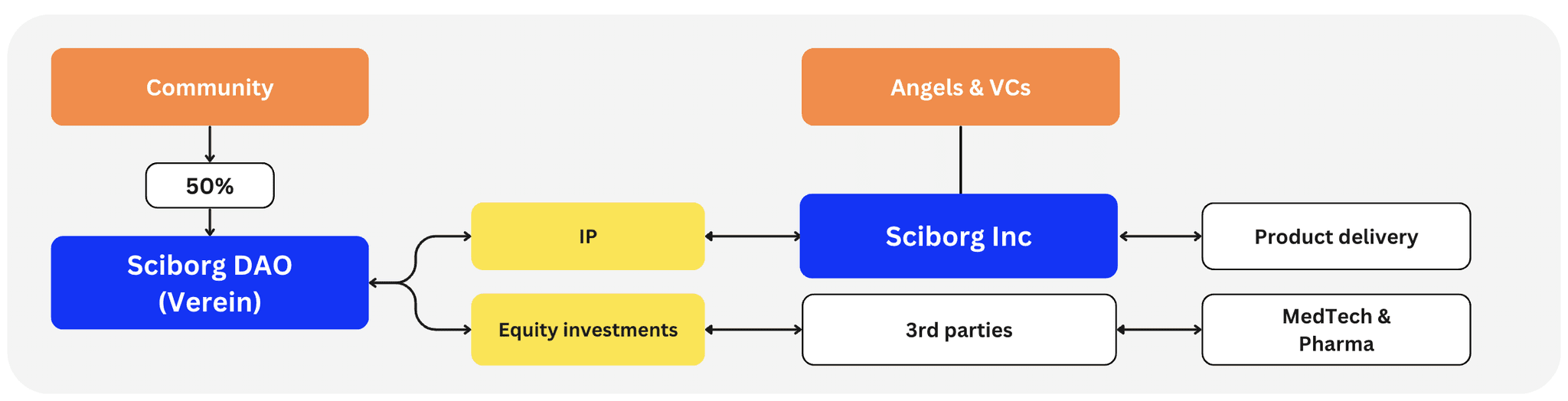

We are not a traditional hard-tech company, nor do we follow conventional approaches. Instead, we channel our efforts and resources through a DAO framework (Swiss Association, Vereln). To align incentives and governance, we will launch the $SCBRG governance token, allocating 50% to the community.

Through the DAO, we will fund research and development focused on survival-critical technologies that other investors typically overlook or underfund. Any resulting IP will be delivered to market by a separate incorporation, Sciborg Inc., or by bridge licensing to MedTech & Pharma. At the same time, we will invest in startups working on technologies that lie on the critical path to cyborgization, who can also exit to MedTech & Pharma.

We recognize we can't develop or influence every essential technology — and we don't need to. Many advancements, like robotics and brain–machine interfaces, already have solid backing. Our role is to identify and support underfunded gaps between us and our North Stars, then integrate those emerging solutions with more mature ones to create a cohesive system: the ultimate cyborg package.

Partners

Longevity Biotech Fellowship

Community of Longevity Accelerationists

CryoDAO

Cryopreservation Research DAO

Hydra DAO

Replacement Research DAO

Vitalism Foundation

Movement to get humanity fight to achieve unlimited lifespans in peak health

Open Longevity

Community against aging, supporting scientific approach to fight it

State of Science

Our focus technologies have wide-ranging applications, from rehabilitation and organ preservation to transplantology and advanced medical devices. Explore our overview to discover the current state of science in these critical fields.

Learn more →Get updates from Sciborg ecosystem

Solve death with synthetic replacements

We unite scientists, engineers, entrepreneurs and investors who seek to prolong and enhance human existence

info@sciborg.xyz

© Sciborg DAO 2024